I do not know Donald Trump. But I know the city that made him, the tabloids that birthed him, the bodega endcaps where his name sat, thick and loud, like an old-school mixtape cover. New York in the ’80s was his kingdom of illusion, his racket of grandiose failures spun as triumphs. And for a time, the rappers, the ones who knew how to make something out of nothing, saw him as just that—gold on the outside, dust on the inside, a mirage of wealth even when the banks came calling.

There is an old Haitian adage—voye wòch kache men—throw the rock, hide your hand. It is a proverb stitched into his being. His life has been an endless performance, a carnival act where the mask is the man and the man is nowhere to be found. He does not tell you what he wants; he dazzles you into forgetting to ask.

A contract is not a promise. An agreement is not a bond. A handshake is only an opening gambit. He does not do business; he does conquest. Every investor, every deal, every hopeful believer is just another mark in a game rigged to feed the only thing that has ever mattered to him—himself.

You want to understand why he suddenly speaks of Panama? Do not look at the canal he pretends to care about; look at his failed ventures, the money that washed through his towers, the oligarchs who saw in him a means to an end.

You want to understand his fixation on Gaza? Do not look at the lives lost, the generational wounds reopened. Look at the land, the possibility of wealth, the deals he imagines himself brokering in a world remade for his benefit.

The windmills? That is not about energy. That is about a golf course in Scotland, about a view he thought he owned and the people who refused to bend for him.

And Obama—no, it was never policy, never ideology. It was humiliation. A joke at a dinner, a room full of people laughing at his expense, a wound to his ego that he has spent over a decade trying to suture with destruction.

The immigrants? It was never about borders. It was always about filth, about his own fear of the brown bodies he does not understand, of the people he cannot control, of the brown hands that built the towers he stamped his name on.

His talent—his singular, devastating gift—is in aligning his personal grievances with the fears of others. He does not lead; he exploits. And the GOP, a party that once prided itself on moral backbone, now bends like a battered lover who knows they should leave but cannot. They are trapped, not by loyalty, not by belief, but by need—financial, social, existential. They have hitched their fortunes to a man who would discard them without thought, and still, they stay.

But something is coming. That much is clear. The center cannot hold. The cracks have been widening, the walls closing in. And at some point, something—someone—will snap.

And when they do, when the reckoning arrives, it will not be quiet. It will be loud. It will be final. It will be the thing he never saw coming.

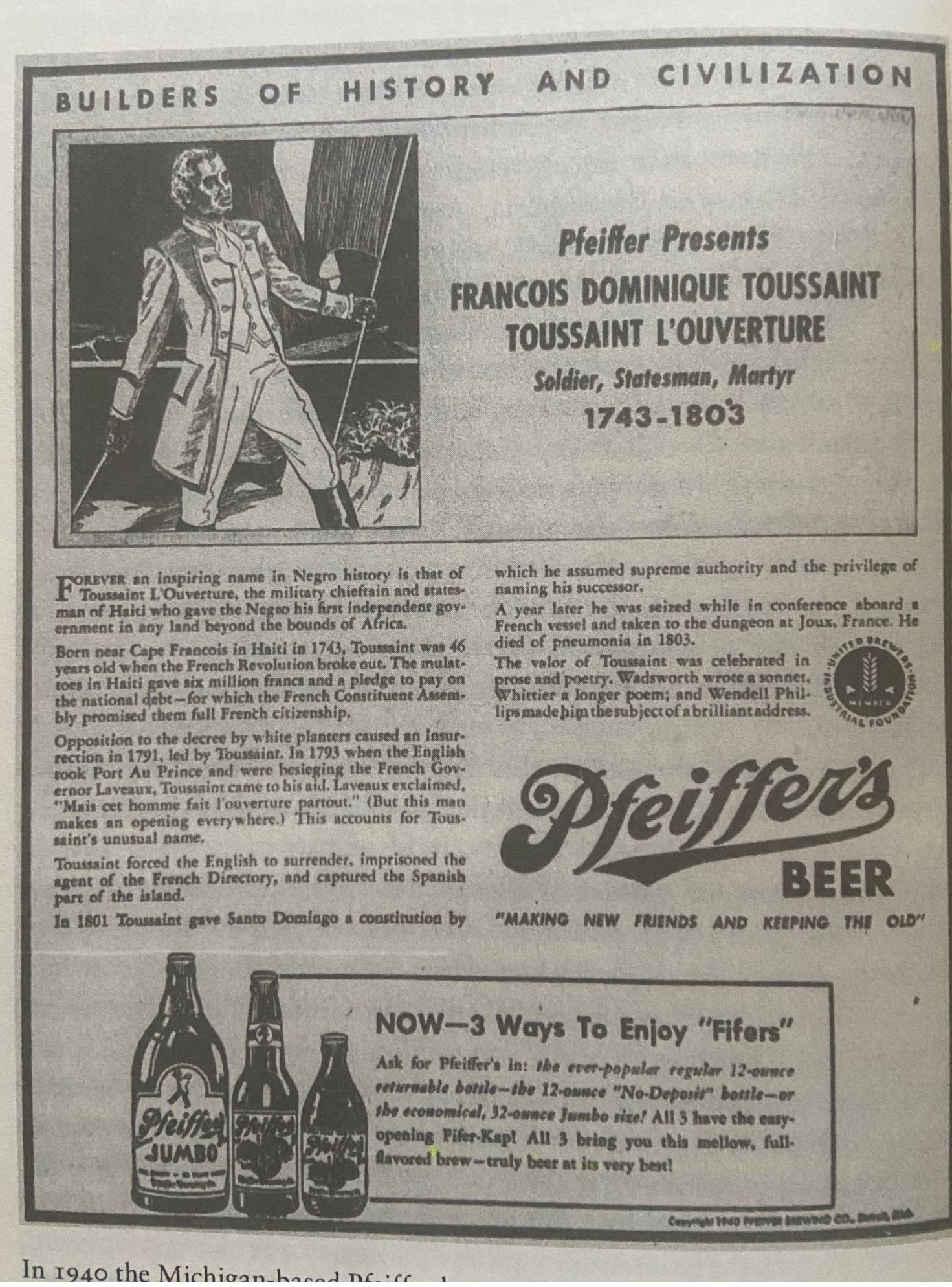

He Was’nt Born in Haiti, but…

He was not born in Haiti, but he could have been. He could have walked the same path as François Duvalier, who turned paranoia into power, who saw enemies in every shadow and purged them before they could whisper his name. He could have been Jean-Claude, inheriting his father’s empire of blood and squander, draping himself in stolen wealth while the country crumbled beneath his feet.

Trump is no ordinary con. He is a trickster of another order, a man who has spent his life not in pursuit of riches but in pursuit of the illusion of riches. He does not build; he brands. He does not earn; he extracts. And in this, he is kin to the tyrants who once drank from the chalice of Haitian sovereignty, who promised grandeur and left nothing but ghosts.

There is an old Haitian adage—Tout sa ki glitè, pa lò. All that glitters is not gold. And yet, how often have we fallen for the shine? How often have we mistaken arrogance for strength, cruelty for discipline, lies for vision? How many times have we, like America now, entrusted our fate to men who see us as nothing more than a stage upon which to perform their legend?

His kingdom is built on sand, his empire on debt. But like all strongmen before him, he understands that the power is not in the lie itself—it is in the willingness of others to believe it. This is why his followers will defend him even as he robs them blind, why the GOP bends to him like broken sugarcane, why men who once called themselves patriots now cower at his feet.

But history does not forget. And history does not forgive. The great deceivers of Haiti’s past thought they could outrun the judgment of time. Some fled into exile, their names spat upon in the streets they once ruled. Others met their fate in the very places they had once called their own. Their statues were toppled, their legacies rewritten not as triumphs but as cautionary tales.

America does not yet understand what it has allowed. But it will. The reckoning will come. Because the thing about strongmen, the thing about those who play at being kings, is that eventually, the people remember. They remember who stole from them, who mocked them, who used them and left them in ruin. And when that remembering comes, it is not quiet. It is not gentle. It is not forgiving.

Haiti knows this truth well. America is only beginning to learn.