What are our origins? Whether it was from civil rights activist Ella Baker who would ask fellow citizens: ‘Where do your people come from?’ Or our Ayiti community who still ask, ‘What’s your family’s name and where in Ayiti are you and they from?’ These rooting questions and stories matter. Let’s think then about the African coasts.

In my classes and community work, our look at Afrique begins with their kingdom formations. Just as I do not embrace the term ‘minority’ as black and brown folk have contributed to global history in major ways; I never, ever, ever begin the stories of Africa in bondage. That false start prioritizes white history rather than ours. We were not captive but rather we were free.

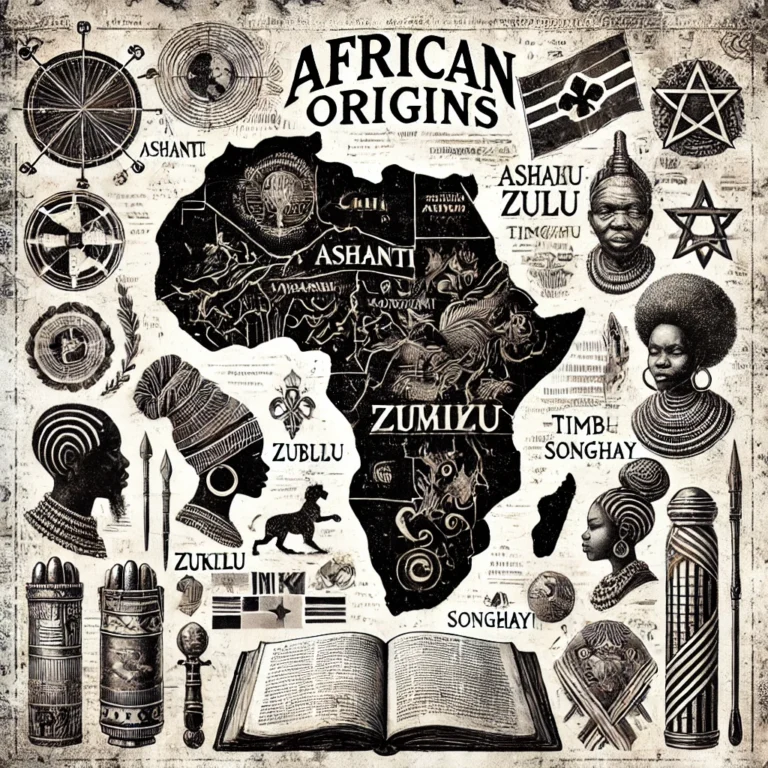

Geographers, Geologists, and scholars from Religious, Archeological, Architectural Studies, and the like keep finding remnants of African nations and their enduring impact, pre-colonial contact. We know the names of the Ashanti kingdom, the Zulus, and the early states of Timbuktu, Songhay, Egypt, and the Akan states. In these spaces, our zanzets traded and mined salt and gold created STEM, recorded their presence, and documented their encounters with the Muslim world and her people, etc.

Three Takeaways

Three takeaways are important as we reflect on our stories. I mention the kingdoms of Ashanti and the Zulu to reference the fact that in the midst of unrelenting European violence on our African continent, Africans still formed nation-states, elected, appointed, and promoted leaders, and survived despite the trifecta of European 1. religious violence, 2. trans-Atlantic trading, and later 3. forced labor for gold, diamonds, and railway work, etc.

We resisted and survived from the beginning through the present. Second, the diversities of people originating from the coastal parts of Africa and the interior contributed to our diversity in the Caribbean. That drum style, the piman (hot spice) that we use, dance moves, braided and loc’ed hairdo, and our acknowledgment of Bondyé (God), our ancestors, the earth, birds and animals come from how our African zanzet interacted humanely with the aforementioned. These are just a snapshot of our look at coastal civilizations from our past.